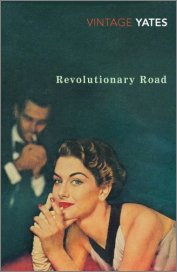

If you don’t know by now that Revolutionary Road was my favorite of all the books I read last year, then you’re just not paying attention. But as I’ve said before, I have my doubts about the film version, directed by Sam Mendes (of American Beauty), which opens in Montreal any day now.

If you don’t know by now that Revolutionary Road was my favorite of all the books I read last year, then you’re just not paying attention. But as I’ve said before, I have my doubts about the film version, directed by Sam Mendes (of American Beauty), which opens in Montreal any day now.

I’m doubtful because the book was such a writerly novel; as much, or more, about the telling as about the story itself. Not that cinema can’t achieve the same level of art and craft in its narrative, but doing it that way generally doesn’t sell a lot of extra tickets, and with Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio in the lead roles, there are some big salaries to cover.

However, I’ve seen a few reviews that indicate the film may indeed be somewhat true to the grindingly anxious subtext and nuance that we find in Richard Yates’s book. But first, Adelle Waldman, writing in The New Republic, provides us with a latter-day review of the novel, reminding us of what’s really going on in the book. Her review’s blurb says “Revolutionary Road, considered the original anti-suburban novel, isn’t actually anti-suburbs–but something far more devastating than that.”

…if Mendes’s new film is to do Revolutionary Road justice, it will transcend the easy anti-suburban categorization. While Yates’s depiction of suburban life is nightmarish enough to exceed the worst fears of Jane Jacobs’s devotees, Revolutionary Road is far more than a complacent takedown of the ‘burbs. It is in fact less an anti-suburban novel than a novel about people who blame their unhappiness on the suburbs.

Katrina Onstad, reviewing the film on CBC.ca, had similar things to say about the book:

… Yates tells the story of a married couple living miserably in the suburbs, but they’ve imported their own pain and dysfunction from the city.

And about the movie:

…their fights are colossal and verbally lacerating, with each party projecting their own failures onto the other. Yates’ clear, colloquial language gets a full workout in these devastating rounds, which measure just how low lovers can go.

There’s more:

Both the book and film take place on the eve of second wave feminism, and April’s rudderless, identity-free existence doesn’t have a name yet; it will take Betty Friedan, in 1963, to identify the plague of discontent felling housewives in The Feminine Mystique. April’s misery may quietly exist in the shadow of what’s coming next, but Mendes doesn’t delve deep into the kind of broad social satire of television’s Mad Men, where housewives regularly disintegrate. There, our pleasure is in watching the racist, sexist characters march obliviously towards the precipice of the late ’60s.

Revolutionary Road is not as moored to its historical moment; there’s actually a timelessness to the psychological portraits Mendes paints. We watch the lit fuse that is Frank and April’s relationship, wondering just how many compromises they can make, how cornered they have to feel before the inevitable explosion.

OK, I’m convinced enough to give it a go. Don’t let me down, Sam Mendes!